Rewriting History: Changing the Archived Web from the Present

Ada Lerner, Tadayoshi Kohno, and Franziska Roesner

Security & Privacy Research Lab, Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, University of Washington

Overview

Web archives such as the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine are used for a variety of important uses today, including citations and evidence in journalism, scientific articles, and legal proceedings. In this work, we explored ways in which an malicious actor might be able to manipulate what users see when they view archived pages of a web archive like the Wayback Machine. We found several different features of the ways that archives host content which allow attackers, under certain circumstances, to deceive users of archives about the way that the web looked in the past. We also perform measurements of the archive, showing that these vulnerabilities are widespread, and explore defenses against these vulnerabilities and attacks.

With this paper, we are also releasing our archival measurement tool, TrackingExcavator, which we used in past work measuring web tracking using archival data, as well as in this work to quantify the prevalence of the vulnerabilities we discovered. You can find links to the code in the For Researchers section of this website.

This work builds on our previous work using archival data to study how web tracking has changed over time, which itself built on past work systematically studying web tracking in the present (see associated software) and developing a new defense for social media trackers (now integrated into the Electronic Frontier Foundation's Privacy Badger tool).

FAQ

What are the attacks described in this work?

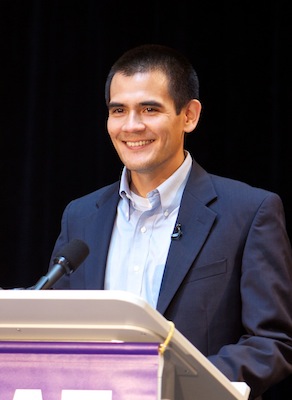

The attacks we describe in this paper allow the potentially malicious owner of particular internet domains to modify the way that people see archived pages in the Wayback Machine web archive (https://web.archive.org). Depending on the particular instance, attackers are either able to take control of specific resources on an archived page (such as a single image) or of an entire page. An example of these attacks is shown in the accompanying images, which show a demonstration attack we launched in which we were able to change the appearance of a 2011 archived snapshot of reuters.com for all users of the archive. In this case, we replaced images and text with implausible replacement content. After confirming that our attack worked, we disabled the attack for ethical reasons.

Attackers using our attacks, or variations on them, may be able to deceive users of the archive about the contents of the web of the past. We emphasize that these attacks do not involve compromising or attempting to compromise the servers of the Wayback Machine or any other entity. Additionally, we describe these attacks as modifying the "view" of the page, as most attacks manipulate what end users see without manipulating the contents of the Wayback Machine's archival database.

The archived snapshot on which we tested one of our attacks.

A screenshot of the original appearance of one headline in the snapshot.

A screenshot of the appearance of that same headline, as modified by our attack.

Our attacks are divided into three types, based on the type of vulnerability that enables them.

- Archive-Escape Attacks: In one type of vulnerability, live web content is mixed inadvertently with archived web content, allowing a modern attacker to inject content.

- In another type of vulnerability, the archive serves content from mutually distrustful sources in a way which allows them to interfere with each other, since they are no longer subject to a standard web browser defense called the Same Origin Policy.

- Finally, in our last type of vulnerability, attackers are able to inject content which replaces missing resources in the archive's databases.

For more details on these attacks and the vulnerabilities which enable them, please refer to the paper

How bad is this?

While we found that a large fraction of archived pages are vulnerable to at least one of our attacks, we emphasize that these attacks can in most cases be launched only by the owners of particular domains. For example, in the attack shown in the screenshots above, only the owner of a particular domain -- projecthaile.com --which was used in 2011 as part of reuters.com is able to launch the attacks. We were able to launch this attack since that domain was unowned, and so we purchased it as a precondition to the attack.

It is important that those who rely on web archives for important use cases, such as for journalistic research, scientific citations, and as evidence in legal cases, be aware of the possibility of these attacks, and that they take precautions to ensure that they are aware of any inconsistencies, whether unintentional or malicious, in the pages they cite and refer to.

I rely on the Wayback Machine -- what should I do?

Our primary advice is to ensure you have the advice of an expert who can help you evaluate the accuracy of any information you use from a web archive. It is possible to detect and/or block many of the types of attacks we describe, and so users of the archive and experts helping them should do so. Our paper describes the attacks in detail, allowing an expert to detect the vulnerabilities we describe. While we did release code for an extension which demonstrates blocking of one type of attack, this research prototype's functionality should not be needed now, since the team which operates the Wayback Machine have already deployed one defensive fix (Content Security Policy headers) which we believe will block the same vulnerabilities our extension defends against -- vulnerabilities to Attack #1 (archive-escapes).

What can the Wayback Machine do about this?

We disclosed our results to the Wayback Machine before publication, and they are being prompt and thoughtful in taking action to mitigate these attacks. They have already implemented Content-Security Policy headers, which instruct client browsers not to load archive-escape content, blocking many vulnerabilities to our Attack #1. We outline other possible defenses in the paper, and we are in contact with the team that operates the Wayback Machine as they consider, design, and deploy appropriate defenses.

Additionally, the team at the Wayback Machine have launched a new feature, described in this blog post, which shows users of the archive the relationship of the timestamps of subresources to the snapshot currently being viewed. The availability of this informaiton will help expert users to better interpret archival snapshots and catch anachronistic requests which may result in benign or malicious modifications to the view of a page.

Is your code available?

Yes, the code for our measurement tool and defensive extension are on Github. See the For Researchers section below.

For Researchers

Our research paper, appearing in ACM CCS 2017, is here.

The code for TrackingExavator, our archival measurement tool, can be found on Github, here.

The code for Archive Watcher, our prototype defense exploring how a browser extension might block our attacks, is available on Github, here.